The History of the Orthodox Brotherhood in Galinotati

The Greek community in Venice has a long and rich history. The presence of the Greeks from the middle of the Middle Ages and especially in the Byzantine period, formed an important cultural and commercial pillar in Galinotati, influencing the development of the city in important areas.

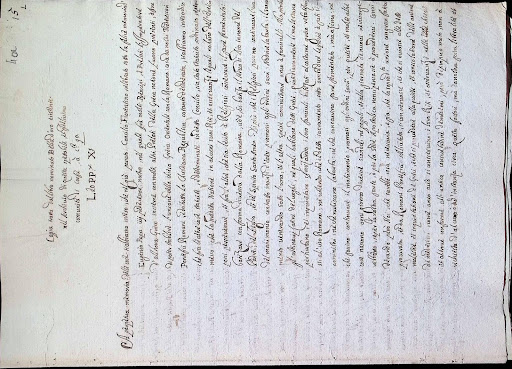

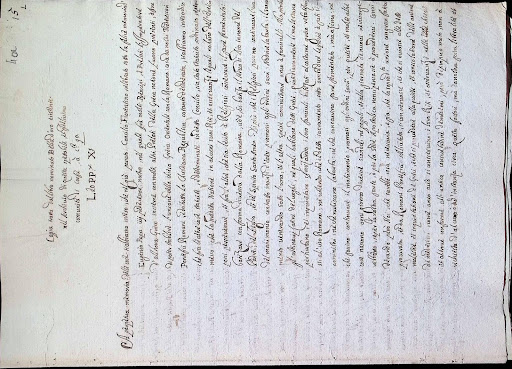

With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, a dynamic centre of Hellenism was created and in 1498 the Greek body of the national minority, “Nazione Graeca”, “the Greek Nation”, was formed, with the Brotherhood being the centre of reference for the Greeks of Venice. The main purpose of its foundation was to provide charitable work, such as the care of the sick and wounded in the war and the relief of orphans and the needy.

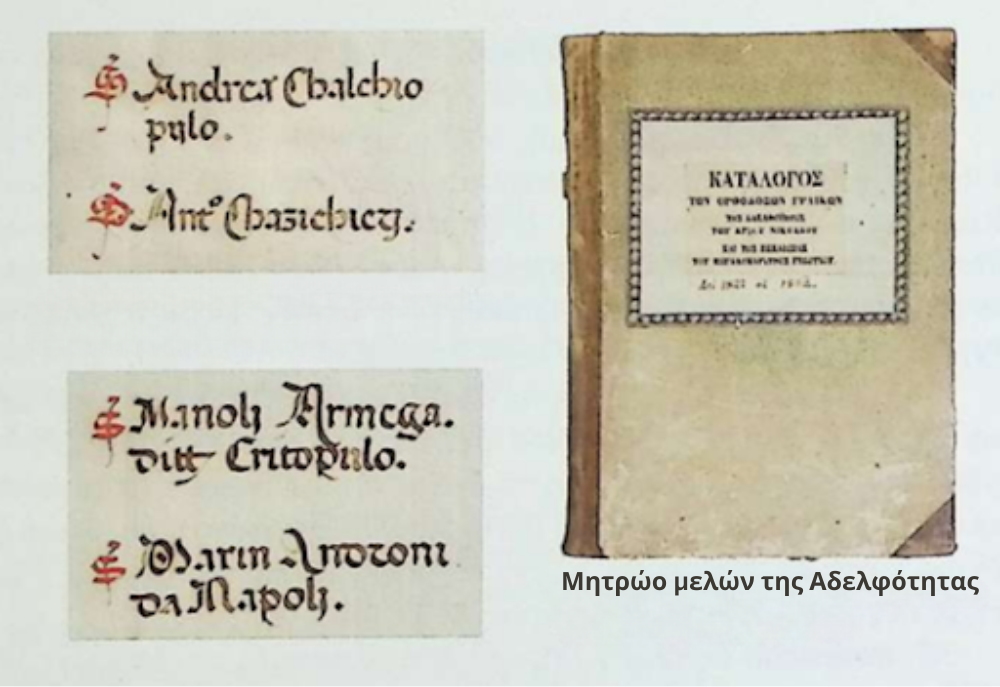

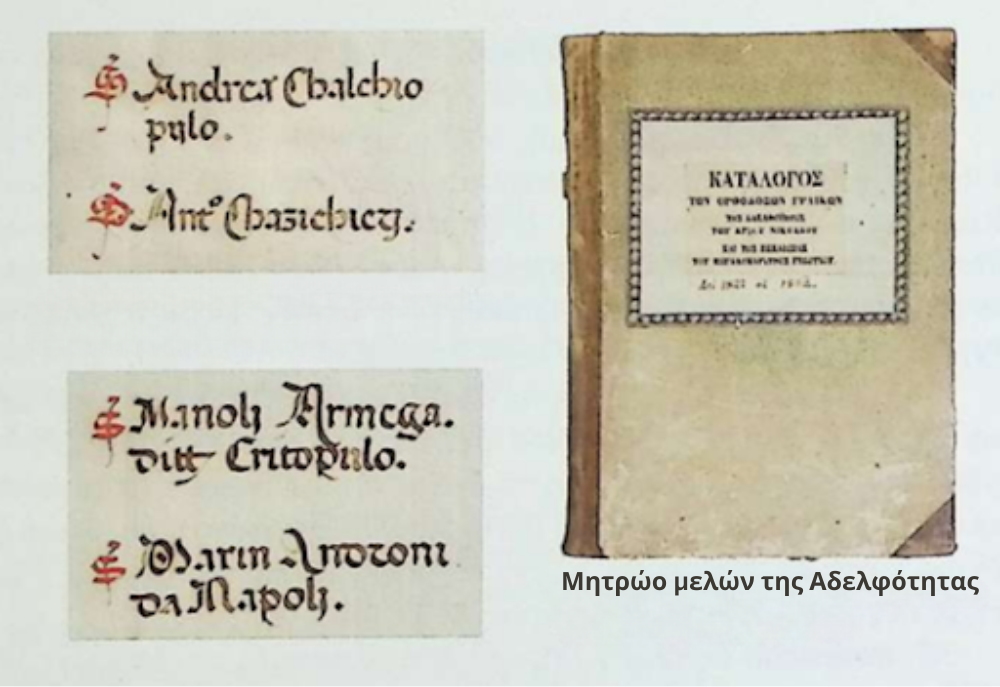

The resources of the Brotherhood came from the contributions of its members, registration fees, collections, donations and bequests. In cases of need, extraordinary contributions and selective taxation were imposed on Greek-owned ships arriving in Venice.

Within the framework of the Brotherhood, in 1593 a school of “Greek and Latin letters” was founded, which was one of the first organized educational institutions for Greeks in the Western world and was an important centre for the learning and preservation of the Greek language and education. For the operation of the school, the Brotherhood received annual financial aid from the Venetian state, which shows the recognition of its role by the local authorities.

The Hellenic Brotherhood continued to play an important role in the community, not only as a religious institution, but also as a social and cultural pillar, with a long-lasting impact on both the Greek community and the multicultural heritage of Venice.

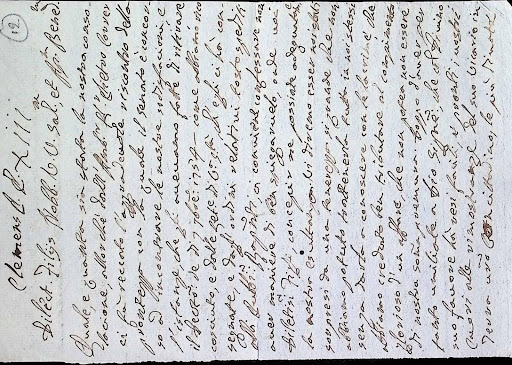

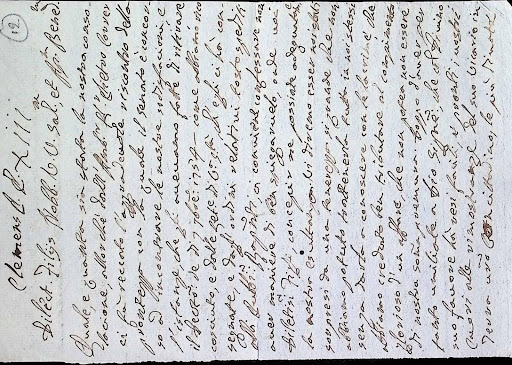

The abolition of the Republic of Galinotate in 1797 by Napoleon was a major blow to the Brotherhood. Its funds, valuables and other assets were seized by Napoleon and were not recovered despite legal efforts. French rule in Venice was soon replaced (by the Treaty of Campoformio in 1797) by Austrian rule, which imposed caution and caution on the members of the community. After a short period, during which the city was annexed to the so-called Regno d’Italia, Austrian occupation was restored.

The decline of the community and the Brotherhood was completed and became final in the following years. The population decline, which had already begun, was accelerated by the settlement of Greeks from the diaspora in the newly established Greek state after 1830.

Thanks to the benefactions of prominent individuals and scholars active in Venice during this period, such as Konstantinos Bogdanos, Georgios Pickering, Georgios Mochenigos and Ioannis Papadopoulos, projects of key importance to the Greek community were preserved. These donations enabled the repair of the church of St. George, the reorganization of the Flanginian College (which provided elementary education and remained in operation with a small number of students until 1907), and, thanks to the Pickering bequest, the renewal of the Brotherhood’s hospital from 1846 to 1900.

The intervention of the Italian state in the affairs of the Brotherhood caused internal strife, and its council was abolished in 1907 and replaced by an Italian provost. By World War II, the Brotherhood had dwindled to just 30 members, but retained much of its property, including its historical and artistic treasures. To protect this heritage, a tripartite agreement was concluded between the Brotherhood, the Italian state and the Greek state.

In 1948, the Italian government allowed the establishment of the Institute of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies in Venice, in exchange for the reopening of the Italian School of Archaeology and the Italian Institute in Athens. The Brotherhood donated its movable and immovable property to the Greek State, which formed the basis for the Institute, on the condition that the Greek State would bear the costs of running the Institute and maintaining the church of St. George.

The fall of Constantinople

The bulk of the Greek population arrived in Venice after the Fall of 1453. People from all walks of life, individually or as families, sought refuge in Venice, mentally following the feelings of cultural proximity captured in the saying of Cardinal Bessarion of Trebizond that 'Venice is like another Byzantium'. The number of refugees was such that according to some reports - though somewhat exaggerated - it amounted to 4,000 people in 1479. The need for survival and security, but also the free exercise of Orthodox Christian worship, were the criteria for the preference of the Greeks, who had already lived side by side with the Venetians in their respective homelands and in Constantinople itself, where there had been a thriving Venetian community for centuries.

The moves of the Greeks for the acquisition of an Orthodox church, which were made while trying to take advantage of any contradictions between the Holy See and the Patriarch of Venice, continued in the following years, but without any result. For this reason they decided to turn in another direction, temporarily abandoning the question of acquiring a church.

Η Κατασκευή της εκκλησίας

The construction of the church began in 1536 and the work was completed in 1577. In the same year, Gabriel Severus settled in Venice as the first Orthodox Metropolitan of Philadelphia. He had served since 1573 in Venice as a parish priest. He then travelled to Constantinople, where he was ordained Metropolitan of Philadelphia in Asia Minor, and from there he was transferred to Venice with the same title, with the approval of the Ecumenical Patriarch. The Metropolitan of Philadelphia is henceforth titled ``supreme and exarch of all Lydia``.

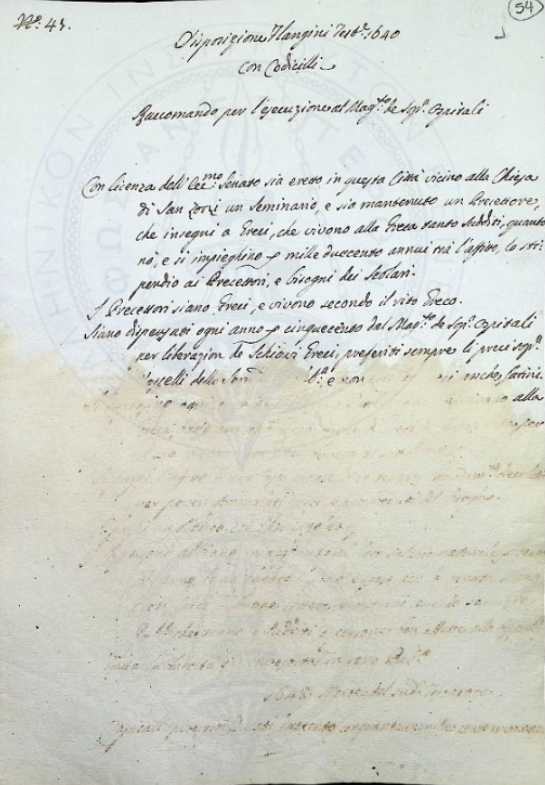

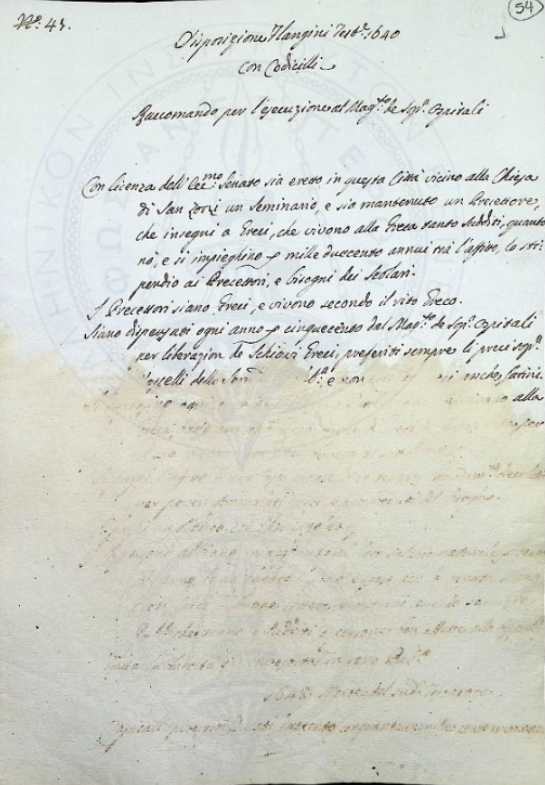

The legacy of Thomas Flaggins

From 1665 onwards, with a bequest from the lawyer and merchant Thomas Flangini, a higher educational institution for Greek students was founded. According to Flangini's will, full scholarships were given to Greek children aged 12-16 for six years of study. The subjects taught were 'humanistic letters', rhetoric, philosophy and logic, theology, mathematics and geography. After graduation, students could continue their studies at the University of Padua.

The Metropolis of Philadelphia

Another pole of cohesion in the world of the Greek community in Venice was the Metropolis of Philadelphia. From the first metropolitan Gabriel Severus (1577-1616) until the fall of Venice (1797), the following metropolitans of Philadelphia served: Theophanis Xenakis (1617-1632), Nicodemus Metaxas (1632-1635), Athanasios Valerianos (1635-1656), Meletios Hortatsis (1657-1677), Methodios Moroni (1677-1679), Gerasimos Vlachos (1679-1685), Meletios Typaldos (1685-1713), Gregorios Faceas (1762-1768), Nikiforos Mormoris (1768-1772), Nikiforos Theotokis (1772-1775), Sofronios Koutouvalis (1780-1790). The successor of Koutouvalis, Gerasimos Zygouras, because his election as a metropolitan was not ratified by the Ecumenical Patriarchate, served the church for thirty years as a ``deposed`` metropolitan only (1790-1820).

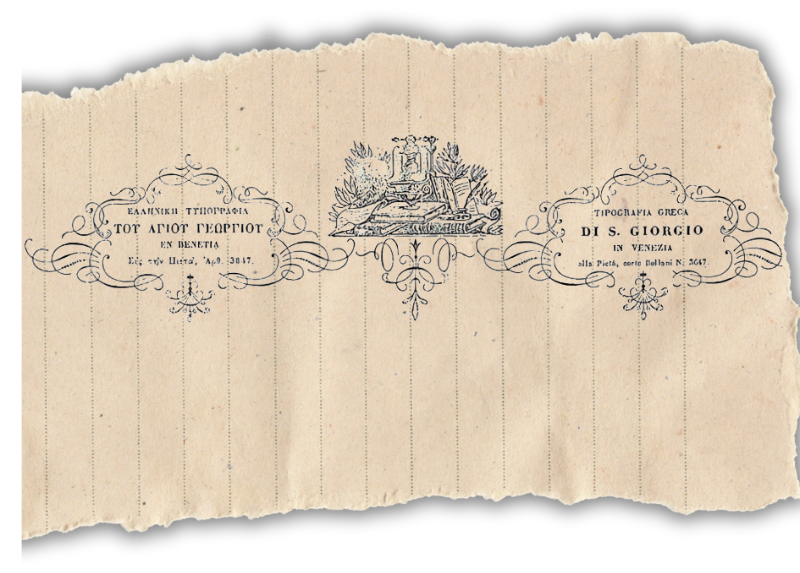

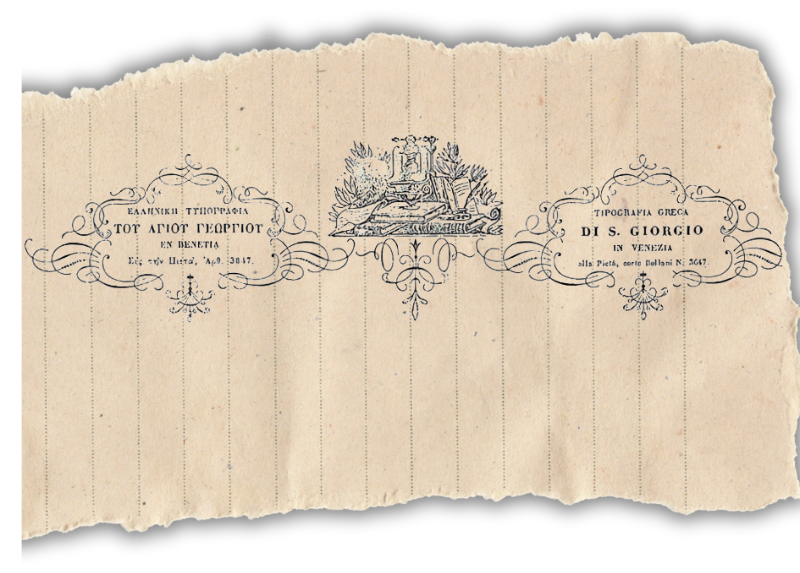

Greek Publications

Venice was the cradle of Greek publishing as early as the 15th century: the first Greek typefaces were created in Italian workshops, Greek publishing houses were founded and a multitude of publications were circulated in Europe and in the Ottoman-occupied Greek regions. In the two centuries before the Revolution, publishing activity peaked. Printing houses of Epirus, such as those of Glyki, Saros and Theodosiou, dominate, some of them being long-standing Greek enterprises.